In 1988, hip-hop didn’t just make noise; it made history. Rob Base & DJ E-Z Rock’s “It Takes Two” lit up clubs and car stereos alike, while Eric B. & Rakim’s “Paid in Full (Seven Minutes of Madness)” remix turned the genre into a playground for sonic experimentation. Public Enemy’s “Bring the Noise” brought urgent political commentary to the mix, and LL Cool J’s “Going Back to Cali” offered a sleek, stylized West Coast daydream. Among them, Salt-N-Pepa’s “Push It” stood as a genuine milestone—a breakthrough for women in rap and, at the time, the biggest-selling hip-hop single to date. Though not on the playlist due to its hit version being unavailable on Spotify, its absence in no way reflects its cultural weight.

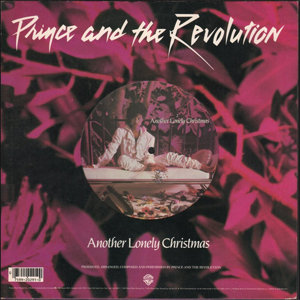

Elsewhere, 1988 was rich in songs that combined sincerity with staying power. Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car” offered social commentary through intimate storytelling, and Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror” turned self-reflection into an anthem. “Wishing Well,” performed by the artist then known as Terence Trent D’Arby, brought soul swagger to the top of the charts, while Prince’s “Alphabet St.” reminded listeners he was still capable of keeping them on their toes. Songs like Kylie Minogue’s “I Should Be So Lucky” and Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up,” both produced by the UK’s Stock Aitken Waterman, were pure pop that have endured far beyond their original chart runs, largely due to their catchiness and an occasional boost from internet-era rediscovery.

Dance floors were equally alive with invention. M/A/R/R/S’s “Pump Up the Volume” and S’Express’s “Theme from S’Express,” the latter missing from the playlist due to its unavailability on Spotify, helped define a new frontier of UK club music that was steeped in sampling and shaped by emerging house and techno scenes.

INXS’s “Need You Tonight” merged rock and funk with a modern sheen, while The Cure’s “Just Like Heaven” and Morrissey’s “Everyday Is Like Sunday” balanced emotion with pop craftsmanship. The Pixies’ “Where Is My Mind?” and Dinosaur Jr.’s “Freak Scene” would prove even more influential in hindsight, while Mudhoney’s “Touch Me I’m Sick” gave an early signal of what would soon be called grunge.

Both the UK and Australia contributed standout tracks that reflected their national scenes’ strength. From the UK, Depeche Mode’s “Never Let Me Down Again” and Erasure’s “Chains of Love” explored emotional depth through electronic textures, while Pet Shop Boys teamed with Dusty Springfield on “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” to bridge classic and contemporary pop. Australia’s Midnight Oil brought urgency and political purpose with “Beds Are Burning,” The Church crafted dreamlike melancholy in “Under the Milky Way,” and Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds delivered stark intensity with “The Mercy Seat.” All three pointed to a vibrant and diverse Australian presence in global music that year.

The year also held room for collaboration, reinvention, and the unexpected. Traveling Wilburys’ “Handle With Care” saw rock legends joining forces without sounding self-indulgent. my bloody valentine’s “You Made Me Realise” hinted at the hazy swirl of shoegaze to come. The Bangles’ cover of “Hazy Shade of Winter” showed that ‘60s source material could thrive in a late-’80s rock context, and Anita Baker’s “Giving You the Best That I Got” offered polished, grown-up soul amid the noisier trends. Nineteen wighty-eight wasn’t about any one genre dominating the conversation; it was about cross-pollination, with club tracks rubbing shoulders with indie rock, hip-hop expanding its reach, and pop songs finding new ways to stick.

Follow Tunes Du Jour on Facebook

Follow me on Bluesky

Follow me on Instagram