Throughout the next however many months I’ll be counting down my 100 favorite albums, because why not. I’m up to number eighty.

When I was in high school in the late 1970s/early 80s, we didn’t have Facebook or Instagram or Snapchat, so we had to rely on other means to learn to hate ourselves. Now one scrolls through their “friends’” feeds of carefully curated photos and stories and sees how everyone else has a better life, what with their socializing and food. At the risk of sounding like a stegosaurus, in my day, I learned about my inferiority in relation to my peers by living in the moment. For me that didn’t lead to self-loathing as much as the gradual realization that my life, like season 3 of Ted Lasso, could be vastly improved.

At the time, I was living in Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Demographically, Englewood Cliffs was white families and George Benson. We were just three miles from the George Washington Bridge, which takes one into Manhattan. Aside from seeing the Broadway shows my parents took me and my siblings to on our birthdays, I saw no reason to go into crowded, noisy, dirty New York City when everything I could want was on our side of the Hudson, or so young me believed. Home to the headquarters of Lipton, makers of the world’s finest tea, and Prentice Hall, the publishing company whose name I noticed in many of my school textbooks, Englewood Cliffs also had a bowling alley and, as of 1973, the Royal Cliffs Diner, which immediately became the hottest spot in town. The diner had a jukebox, with speakers attached to the wall at every table, so you could select your favorite tunes and all of the patrons would get to enjoy your choices blasting at their table. Already blessed with impeccable taste, I would feed the machine quarters and select the grooviest pop songs of those years: Barry Manilow’s “It’s a Miracle,” ABBA’s “SOS,” Diana Ross’s “Love Hangover.” The list goes on and on. There can be no doubt that my choices enlivened everyone’s meals. Even then I had my finger on the pulse of what was new and exciting in the world of music. I listened to Casey Kasem count down the hits every Sunday morning and loved everything that made the top ten, except “Cats in the Cradle,” that downtempo dirge about looking back on one’s life with regret, something eleven-year-old me couldn’t identify with. Now that I’m older, I get it. Regrets? I have a lot. I understand the pain of the guy in the song, but that doesn’t mean I want to hear it. If you gave me the choice between listening to “Cats in the Cradle” or having knitting needles jabbed into my eardrums, I’d say “Put the yarn to the side for a moment.” Maybe for Christmas someone will get a nice sweater with a bit of my brain tissue on it.

Englewood Cliffs didn’t have its own high school, so around half of the students with whom I attended elementary school went to private schools in nearby towns, while the rest of us attended Dwight Morrow High in Englewood, the bigger and less affluent town next door. The student body there was an even mix of Black and white, with a sprinkling of Latinx and Asian kids.

For my junior and senior years of high school, my parents decided to send me to Saddle River Country Day School, a fancy private school that was supposed to provide me with a better education.

Saddle River Country Day School was a paragon of diversity. We had kids from all walks of life: rich and white, less rich and white, and even less rich and white. There were also some non-white kids, and I’m proud to tell you I was friendly with 100% of the Black kids at the school. Before you compose a letter to the NAACP urging them to present me with the award for Ally of the Year, I probably should mention that our school had only three Black kids. Okay, you can write that letter now.

Unlike at Dwight Morrow, where one could attend class in hot pants and a tank top (shout out to Leslie W!), at SRCDS we had to dress like we were attending a Fortune 500 business presentation. Female students had to wear skirts or dresses that went below the knee to cover their sinful legs. Boys had to wear jackets and button-down shirts and ties and slacks. Jeans were verbotten. The goal was to prepare us for the real world, which by this time I realized was a very distant second to the fantasy world in my mind, where I and my wife, Olivia Newton-John, were on a never-ending world tour, singing duets and donating half of our proceeds to animal-related charities and social justice causes, dressed comfortably in jeans and t-shirts. I wore a jacket and button-down shirt and tie and slacks on my first day of work at CBS Records. The stares I got from fellow employees made me realize how ridiculous I looked. My second day there I went to work in a t-shirt and jeans and instantly felt like I fit in, though I knew that it was only a matter of time before I left that job to hit the road with Olivia Schwartz. (SPOILER ALERT: It didn’t happen.)

Saddle River Country Day School was a bastion of white privilege. Its students and teachers screamed white supremacy. Not literally, although Mrs. Hart, the typing teacher, had an affinity for a particular racial slur that she managed to effortlessly squeeze into conversations, no matter the subject. She could be remarking about the weather or telling us what she had for breakfast or instructing us where to place our fingers on the typewriter keys and somehow she’d drop that word in there like it’s a perfectly normal thing to say, while I sat there in stunned silence. I was too obedient? shy? shocked? to tell her using that word is wrong, though I had the feeling she’d been told that already at some point in her life. Clearly she had no concerns about ever winning that Ally of the Year award.

Mrs. Hart may have had a kinship with our history teacher, Mr. Revoir. Though I never heard him utter a slur, he wrote in my yearbook “The south will rise again!” I’m not sure how that was supposed to inspire me or make me feel good about my future, though I should add that in his note, rather than addressing me as Glenn, he called me Hamburger Helper, a nickname I never had, so it’s quite possible that Mr. Revoir was insane. I will say this for him: his perspective on events in US history was very different from what I’d learned at Dwight Morrow.

One day, I was in the office of Ms. Demarest, our school’s Dean, discussing my college prospects. As we were talking, we heard a student in the hallway use the s-word. (Shit.) I chuckled, because that’s comedy to a high schooler. Ms. Demarest gasped and ran out of the office like a fireman responding to an alarm. She reprimanded the indecent, God-hating probable arsonist, assigned him detention, and told him this is going on his permanent record. Because in this school, you’re not allowed to say the s-word. Ain’t that some shit?

SRCDS was a 40-minute drive from my home, so a minibus would collect me and some other students from nearby towns. Our bus driver was a rocker dude with long hair and an appetite for thrills. On the way home from school he would challenge other drivers on Route 17 to race, even though a minibus has never won the Indianapolis 500. He gave it his all, stepping on the gas, weaving in and out of traffic, seldom using the shoulder to pass other vehicles. The other kids would cheer him on. They thought he was cool and fun. I thought he was reckless and deranged. One day he got pulled over by a persnickety cop with no real crime to fight, who asked him two ridiculous questions: “Did you know you were driving 70 mph?” and “Are you aware you’re driving a bus of teenagers?”. What did he think the driver would answer? “Duh! It’s not like I can make this bus go any faster than 70, and the sooner I get these brats home, the happier all of us will be.” Or “No, I had no idea there were teenagers on this bus. I thought they were just some noisy hallucinations from the acid I dropped this morning. (turns around) Holy Christmas! How did you guys get in here? Are you real? Is this pig real? Is anything real, really?” What was real was the speeding ticket he got. Though he was reckless and deranged, I felt sorry for him. He probably didn’t aspire to be a bus driver for a bunch of spoiled high schoolers. Maybe he dreamed of being Bobby Uncer, the famous race car driver (or was Bobby Uncer a hockey player? I don’t know. I don’t follow either sport. For all I know a minivan has won the Indianapolis 500.).

I got my driver’s license during my senior year, and my parents let me drive to school in the car that we usually kept at our second home in the Poconos. (Yes, my family had a second home, a modest three-bedroom cabin in the mountains where my parents could go to escape the stress and pressure of an upper middle class suburb.) The car was a Ford Pinto, a model notorious in the late 70s for its susceptibility to exploding into a ball of flames should it get rear-ended. I parked in the school parking lot, where my car stood out among the Mercedes Benzes and Corvettes and Camaros. As I got out of my car the first day I drove it to school, a fellow student smirked and said “A Ford Pinto. Your parents must really love you.” Yes, they love me so much they let me use a car that with a slight tap could take me out of this hellish school, away from your opinions and superficiality and snobbery. I tell you, reader, I looked forward to that day when I wasn’t surrounded by people with that attitude, though preferably not by becoming a human inferno.

Later that school year, my dad decided to soup up the car, not to spare me the ridicule of driving something so uncool, but because he was into sporty cars. He was driving a Ferrari at the time, or maybe that’s when he had his Maserati. He painted the Pinto black, added black louvers to the rear windshield, and put a giant decal of a horse on the front hood. He thought it looked hip, but it looked like a Ford Pinto with louvers and a horse decal. Whatever. As long as it got me to where I wanted to go, I was happy. To me, a car is a car. To my parents, a car is a status symbol. Years later, when I moved to L.A. to take on a Vice President job at a major company, my mother told me “Be sure you have a nice car to show everyone you made it.” “Wow, look at that Pinto with the louvers and the horse sticker! Must be the chairman of Paramount or a Rockefeller!”

SRCDS offered a range of clubs and activities for the students to join, most of which I had no clue existed until I looked at my yearbook while writing this. There was the Needlework Club, the Aerobic Dance Club, the Ski Club, The Strategic Club (about what they strategized I have no idea, which may be for the best) and The Algebra Clinic, who probably partied with 2x/y kegs of beer. The senior with the most clubs and credits and awards under his name in the yearbook was Jeff K, the headmaster’s son. While your school had a principal ours had a headmaster. Don’t act surprised. My list of accolades was more modest. According to the yearbook, I wrote for the school newspaper (I have no memory of that, or of the newspaper itself), I was on the staff of the school literary periodical (I have no memory of that, or of the periodical itself), I was on the Honor Roll (once), and I was in the school play. That I remember! The play was Fiddler on the Roof, a musical about Jewish peasants in Russia. I played Motel the tailor, who marries Tzeidel, the daughter of Tevye, the milkman. Tzeidel was played by my best friend Laura, who is still my best friend today, though she has since upgraded her husband.

Laura and I both transferred to SRCDS from Dwight Morrow High School the same year, and having that in common made us instant friends. Besides play rehearsals after school, we’d go to the movies on Saturday nights and then stuff our faces with stale cake at the Royal Cliffs Diner. Their jukebox was always up to date. In the fall of 1980 they added John Lennon’s new single “(Just Like) Starting Over,” which was all well and good, but we preferred the flip side. It was Yoko Ono’s “Kiss Kiss Kiss,” a new wave song before new wave was called new wave, consisting of much moaning and groaning, with Yoko bringing herself to orgasm in the last thirty-nine seconds. We played it over and over again, with the sound of Yoko’s climax emanating from the speakers at each table, making the Royal Cliffs Diner sound like Plato’s Retreat at 2 AM on a Saturday. The town hadn’t been so scandalized since George Benson moved in. (I know there are a few of you who are too young to know what Plato’s Retreat is, so let me explain: Plato was a Greek philosopher/influencer a few hundred years before the birth of Christ. Every summer he and some friends from the gym would rent a house in Mykonos, where they’d often throw parties, blasting disco tunes such as “(Push Push) In the Bush” and “Love To Love You Baby” and shooting music videos to go with them, which Plato would upload to his Tik Tok account, which earned him a sponsorship deal with Red Bull. His legendary parties became known as Plato’s Retreat.)

While I was living in the modern world and grooving to Barry Manilow and ABBA and Diana Ross and Yoko Ono, my classmates were stuck in the past, worshipping The Grateful Dead and The Doors. No, not worshipping. It was more than that. Exalting? Revering? Venerating? For our prom, they went all out and hired a Doors tribute band. And guess what our prom theme was! “Riders on the Storm!” That sounds as festive as a funeral. It’s a slow and gloomy song about a serial-killing hitchhiker. Pass the punch and party on! Even worse, you can’t dance to it! An uptempo song about a serial-killing hitchhiker I can work with, but this? Did my privileged classmates connect with the character in the song – the loner who feels like an outsider in reality? I was the outsider! I was the only one there who hated The Doors! But I kept my mouth shut, because my date, Andrea, was on the prom committee and had picked the band. Imagine if we went with my idea for a prom theme – Diana Ross’s then recent hit “It’s My Turn.” That would’ve been perfect! We were about to graduate, it was our turn to shine, and that song would’ve captured the moment beautifully. But no one bothered to ask me, and I’m pretty sure if the Diana Ross song was our prom theme, Mrs. Hart would have had a stroke.

“And to the graduating class of 1981 I say: Break free from the cocoon and spread your wings. Find your own path in this crazy world. Life is too short to conform to what others expect of you. Embrace who you truly are, with all your quirks and passions, and march to the beat of your own drum. Say ‘Au revoir’ to Mr. Revoir, ‘Adieu’ to Ms. Demarest, and ‘Sayonara’ to Saddle River. Explore new horizons and discover your own passions, unburdened by the opinions of others. Delve deeper into your interests, and carve out a place where you truly belong. I’m talking to you, Glenn Schwartz.”

- From the commencement speech I gave to myself

*****

April 2012. It was a typical beautiful day in Los Angeles, where I’ve lived since 2003 when Warner Music moved me from New York City to head up their Licensing and Contract Administration departments. In that role I was responsible for making deals for the recordings in the Warner Music catalogue, a catalogue that includes the classics “Riders on the Storm” and “Cats in the Cradle,” as well as more uplifting fare like “Tears in Heaven” and “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now.” I was driving my BMW along Mullholland. (Look everyone! I made it!) The convertible top was down, and I was listening to one of the hip hop stations on satellite radio. (In the more than three decades since graduating high school (sidenote: fuck) I’ve gone from jamming exclusively to top 40 tunes and the odd Yoko Ono number to grooving to a far more expansive and eclectic mix of music, as I broke free from my cocoon and explored new horizons. It’s not surprising to hear me pumping hip hop or punk or even some country music. Still, “It’s a Miracle” by Barry Manilow remains the bomb.) A song came on that grabbed my attention like a clown with a chainsaw. It opened with an entrancing vocal sample, a sweet voice crooning “smoking weed with you ‘cause you taught me to.” Soon a rapper told how people come to L.A. for “Women, weed and weather.” I’d heard the song before, back in the office during one of our Monday morning meetings, when my department discussed moving forward with the request to license that hypnotic sample, which is from the Warner catalogue, for this new recording by a young artist named Kendrick Lamar. The song didn’t make a strong impression on me that first time, maybe because I was too focused on figuring out what to charge for the license. But hearing it again, while driving in Los Angeles on a beautiful day, made me appreciate it more. It was a catchy song, even if two of the three things Kendrick said people love about L.A. don’t apply to me. I don’t smoke weed, and I don’t like women. Well, not in that way. Like I said, I’ve changed since high school.

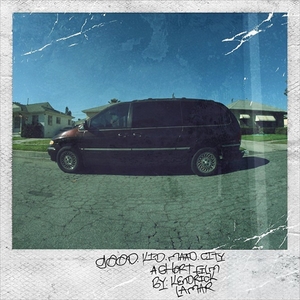

Though that song, “The Recipe,” served as the first single from Lamar’s major label debut album, good kid, m.A.A.d. city, it only appeared as a bonus track on the album’s deluxe edition. The proper album, presented on its cover as “a short film by Kendrick Lamar,” is an autobiographical journey portraying the struggles and aspirations of a Black 17-year-old growing up in Compton, a place worlds apart from Englewood Cliffs. Compton has a vastly larger population, nearly half of whom identifying as African American, with a greater percentage of its residents struggling through the hardships of poverty. The city has no bowling alley or diner, so a teenager must find other diversions. Throughout the album, Kendrick wrestles with the temptations and pressures of gang culture, drugs, violence, and peer pressure, while also seeking a higher purpose. Will he accept his fate as a kid from Compton or break free from its grip? Me at that age: does this tie go with this shirt? I don’t want to get any shit flak from Ms. Demarest.

On the track “m.A.A.d. city,” Lamar ponders if he should join a gang, knowing that doing so would make him a target for gun violence, while not doing so would leave him without protection. There’s much more gravity to his position than high school me pondering if I should join the Blue Key Club (which I had no clue existed until I looked at my yearbook while writing this. I can’t even imagine what they did there.)

On the cut “The Art of Peer Pressure,” Kendrick admits that he acts differently with his friends, doing things he normally wouldn’t do, like smoking, drinking, and robbing. He comes to realize that this is not the way to freedom. In contrast, my most mischievous activity in the comparable period in my life was playing Yoko Ono’s new wave orgasm on the Royal Cliffs jukebox, which, when I think about it, was a way to freedom.

On “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” Kendrick embraces his individuality and expresses the need for others to respect his journey. He is optimistic (“I can feel the changes / I can feel a new life”) and ambitious (“You can remain in a box / I’ma breakout and then hide every lock”) as he aspires to find his own path. Seventeen-year-old me was optimistic I would get accepted into a decent university, the path of all of my high school peers.

On “Poetic Justice,” named after a Janet Jackson movie and built around a Janet Jackson sample, Kendrick uses the metaphor of a flower blooming in a dark room to express finding hope in a harsh reality. My reality wasn’t as harsh. My most challenging decision was picking which Broadway show to attend for my birthday.

On “Swimming Pools (Drank),” Kendrick raps about the prevalence of alcohol in his family as a means to numb the pain and forget reality, ultimately not seeing that as a path for himself. In contrast, my family wasn’t much into drinking, and my concerns were centered around whether I should join them for a weekend at our home in the Poconos.

“Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst” lays bare Kendrick’s vulnerability as he reflects on his impact on others and wonders about the legacy he’ll leave. On the cut, Kendrick witnesses the death by gunfire of his friend Dave. Dave’s brother, vowing to avenge his death, says to Kendrick “If I die before your album drop, I hope —,” his thought cut short by the sound of gunshots. Kendrick yearns to escape the cycle of violence surrounding him and make a positive change. I’m guessing that at 17 my idea of legacy was the articles I was allegedly writing for publication in my school’s alleged newspaper.

From those song descriptions you might think that listening to this album would be a depressing experience, but it’s not. It’s actually quite exhilarating to hear this relatively new-to-the-scene rapper’s way with words (including Mrs. Hart’s favorite) and vocal gymnastics and imagery and flow as he paints a vivid picture of his life and struggles. Drawing from various musical genres and influences, he creates a fully-realized piece of art. The album’s critical and commercial success (a Grammy Award nomination for Album of the Year and certification for over three million units sold in the US alone) serves as proof that one can attain extraordinary heights of achievement by steadfastly following one’s personal artistic vision and staying true to oneself.

Was I the role model Kendrick looked to to see that one can carve their own path and have dominion over their future? The answer is obvious. We both turned our hobbies into careers. We both found our own identities. We both escaped our environments. I did so before him, so duh.

Not only does Kendrick look up to me, but I look up to him. We have a connection, as I, too, was once an adolescent who wanted to break away from what my peers were doing. Sure, my peers were rich snobs who wore suits and chased fancy high-paying white-collar jobs, while his peers were not born into wealth and resorted to making money via arguably less savory means, but other than that, we’re practically twins. It’s the power of choices and the drive to seek a better path that connects us. I’m proud to call him my friend. (Clearly my fantasy world remains alive and strong.)

Kendrick and I do have some differences, though. For one, he is extraordinarily talented, while I am…I don’t wish to say hopelessly untalented, or remarkably incompetent, or spectacularly unskilled, or hilariously inept, or astonishingly awful. I’m just not Album of the Year nomination material (though I shouldn’t sell myself short, for that award was once won by the band Mumford & Sons, whose music, per the I Hate Mumford & Sons Facebook group, consists of “euphoric banjo anthems sung by annoying upper class waistcoat sporting husky little fucks”). Also, while I, like Mumford & Sons, seek and fail to get validation on social media, Kendrick avoids reading about himself on Facebook as he wishes to keep his ego in check. That said, he does rap “I love myself” on one of his standout tracks. That track isn’t on good kid, m.A.A.d. city. It’s on an album that’s coming up on this list.

Follow Tunes du Jour on Facebook

Follow Tunes du Jour on X

Follow me on Instagram